Fully Diluted Market Capitalization, commonly referred to FDMC or Fully Diluted Value (“FDV”) in crypto, is a stock market concept contorted into crypto. The concept was introduced to capture the dilutive nature of protocols. Its use today is flawed and in need of an update.

This article explores the fallacies of crypto’s ‘fully diluted market cap’ concept and suggests an alternative.

A little history…

Market capitalization represents the equity value of a company traded in public markets. It equals a company’s share price multiplied by the number of shares outstanding. The rise of tech companies in the 1990s gave rise to stock based compensation. Companies started paying their employees in stock options. There are several benefits to stock compensation. It aligns company and employee incentives. It’s a non-cash expense. It has an advantageous tax treatment.

Stock based compensation, until recently, was not reflected in a company’s income statement nor is it a cash item on a company’s cash flow statement. It was an expense that didn’t show up anywhere. But it eventually does in the number of shares outstanding. As the share count grows, the earning per share, all else equal, declines.

Investment analysts adjusted for the phantom stock based compensation expense by adjusting the number of shares outstanding. Analysts added the future shares that would be issued to employees to the existing number of shares outstanding. The sum of the two became known as the fully diluted share count. The fully diluted share count multiplied by the share price produced the fully diluted market cap. Fully diluted share counts and market caps are commonplace in equity investing today.

…Applied to crypto

A similar market cap concept applies in crypto. A protocol’s market cap is the token price multiplied by the number of circulating tokens. The number of circulating tokens is essentially the same as the number of shares outstanding. However, unlike the number of shares outstanding for a company, the number of circulating tokens for a protocol regularly increases materially.

Companies prefer not to issue shares. Issuing shares is equivalent to selling equity in the company at the current stock price. If a company is constructive on its future, then why sell equity at today’s price? Doing so dilutes the value of the existing owners.

Protocols, on the other hand, regularly issue additional tokens. Token issuance is part of their ‘business plan.’ It all started with Bitcoin. Bitcoin miners ensure transactions are correctly inputted on the Bitcoin blockchain. They are compensated in bitcoins. As a result, the Bitcoin network needs to continually issue new bitcoins to remunerate the network’s miners. The blockchains that came after Bitcoin followed the same model: issue native blockchain tokens to reward those that accurately input transactions.

The token issuance model, inherent to blockchains, means there are continually more tokens outstanding. Crypto market cap didn’t capture the future number of tokens outstanding. The fully diluted market cap was developed to do so. The fully diluted market cap is the product of the current token price multiplied by the total number of tokens that will be issued. For protocols that have a continually inflating number of tokens, it is customary to use the token supply figure in ten years time.

FDMC sort of made sense

People correctly realized that the crypto market cap didn’t tell the whole story. A different measure was necessary to capture the impact of all the future tokens that would be issued.

At the same time, the ‘business plan’ of protocols evolved. New token issuance was no longer only to reward miners, as was the initial case with Bitcoin. Tokens were also issued to develop the network. Token issuance could help bootstrap a network to its functional utility. A network, be it Facebook, Uber, Twitter or a blockchain, doesn’t have much utility unless lots of other people use it. But few people are interested in being the early users. Issuing tokens to early adopters gave them a financial incentive to use and promote the network until others joined and the network itself had utility.

Token issuance also became a form of compensation for the enterprising developers that built the protocols and the venture funds that backed them. There is nothing wrong with rewarding entrepreneurs, the ventured funds that back them and early adopters. The point is that token issuance became more complicated.

But FDMC has shortcomings

The logic of FDMC is riddled with flaws.

1. The math is wrong

Somehow the crypto market understood that if a protocol issued more tokens then it should be worth more. That’s just plain wrong. There is no example in business, economics or crypto where issuing more of a thing makes the individual thing more valuable. It’s simple supply and demand. If there is more supply, with an unmet demand, the thing is worth less.

The FTT token is a prime example of the falsehood. FTT is used as an example because it offends the fewest people. Its token construct and mechanics, however, are similar to others. The price of FTT was $25, prior to FTX implosion. The market cap was $3.5 billion with 140 million circulating tokens. The fully diluted market cap was $8.5 billion with 340 million total outstanding supply.

So by issuing an additional 200 million tokens, a 2.4x increase, the market cap of FTT also increases by 2.4x…huh?

How does that possibly make sense?

It doesn’t.

For the FTT FDMC to actually be worth $8.5 billion, then the incremental 200 million tokens issued would have to be sold to buyers at the current price of $25. But they’re not. The incremental 200 million tokens issued are simply given away. There are no proceeds from the issuance.

The table below illustrates the difference in FTT market cap and token price if the 200 million FTT tokens are issued compared to sold. The token issuance simply adds 200 million tokens to the existing token supply, resulting in 340 million fully diluted tokens outstanding. The token issuance has no impact on the FTT market cap. The pro forma impact is a 143% increase in tokens outstanding and a 59% decline in the price per token. It’s simple math. The numerator is constant and the denominator increases. The resulting quotient is a smaller number.

Alternatively, if the 200 million FTT tokens were sold at the then current token price of $25, then FTT would receive $5 billion in proceeds, which would increase the market cap to the fully diluted market cap value of $8.5 billion. The number of tokens outstanding would increase to 340 million. Both the market cap and tokens outstanding increase by 143%. The net result is no change in the price per token.

Stocks operate in the exact same way. If Apple issues more shares to employees in the form of stock based compensation, it does not receive proceeds. The resulting impact is an increase in the fully diluted shares outstanding and thus a lower lower price per share. If Apple sells shares to the market at the current price, it receives cash proceeds. Its market cap increases by the amount of proceeds. Its shares outstanding increases by a commensurate amount. The net result is no change in its share price.

Applying the crypto fully diluted market cap logic to stocks highlights its fallacy. If the logic held, then every company should issue more shares to increase its fully diluted market cap. That clearly does not happen. Taken to its logical conclusion, the fully diluted market cap of each company is infinity. There is no cap on how many shares companies can issue. Therefore, every company, no matter the size, growth profile, profitability and return on capital, should have the same fully diluted market cap; infinity. That also is clearly not the case.

What about deflationary protocols?

Most protocols are inflationary meaning they issue more tokens over time. Some protocols are, or will become, deflationary meaning in the future there will be fewer tokens outstanding. Deflationary protocols are worth less in the future than they are today according to crypto’s FDMC logic.

Huh?

There will be less of a thing in the future, yet as a result of there being less of it, the thing will be worth less. That doesn’t make sense. It’s contrary to basic economic principles of supply and demand.

2. It implies the impossible

The crypto FDMC logic implies the impossible. If the FTT FDMC is $8.5 billion, while the market cap is $3.5 billion, then the market implies that each recipient of the incremental 200 million FTT tokens issued will create $5 per token of value as soon as the additional tokens are received. As explained, there are no proceeds from the 200 million token issuance. Therefore, the only way to achieve the $8.5 billion FDMC is if those who receive the 200 million tokens issued create $5 billion of value overnight.

But how are they going to do that?

How does putting more tokens in the hands of people increase its market cap? It doesn’t. The tokens likely sit in a wallet as part of an investment portfolio. The recipients do nothing with the incremental tokens other than trade them.

3. Unintended consequences

The unintended consequence of crypto’s FDMC logic is overstating the value of protocols. Investors, rightly or wrongly, tend to believe that the larger the market cap of an asset, the more valuable and stable it is. Investors took comfort in the large FDMC valuation of these protocols often without realizing the flawed logic of the fully diluted market cap calculation. Few are more guilty of this than FTT.

FTT traded over $50 per token with a market cap of $7 billion and a FDMC of $17 billion. Yet during that period the average daily trading volume in FTT was rarely more than a couple hundred million dollars.

Big FDMC, small market cap and tiny trading volume is the recipe for disaster. Some tokens executed this model in the height of the crypto market. The setup enables market manipulation. A small trading volume allows a few parties to control the trading volume and hence the price. The token price sets the market cap and ultimately the FDMC. It meant that tokens that barely trade, or are wash trade, support artificially high token valuations that get extrapolated into enormous FDMC values. It’s wrong and disingenuous. The exaggerated values were used as collateral for loans. It also obfuscated the actual size of what was being invested in.

To understand how FTX orchestrated such a high value for FTT and what it enabled FTX to do read F'd TX: The Saga.

High FDMC and low market cap assets are less prevalent today. The market is more discerning of this red flag. But they do still exist. The table below lists the number of protocols whose FDMC trades at a given multiple of its market cap.

4. Token issuance looks increasingly like stock based compensation

The purpose of token issuance has come a long way since Satoshi wrote the Bitcoin whitepaper. Issuance is used for a variety of purposes beyond rewarding network miners and validators.

Token issuance increasingly looks like the crypto equivalent of the equity market’s stock based compensation. Protocols reward people who build their network by granting them the protocol’s native token, just like a company grants employees, advisors and investors stock options to reward them for building the company.

Token issuance should be viewed in a similar lens as stock based compensation. Issuing tokens, just like issuing shares, is a cost to the protocol or company. It is dilutive to the number of tokens or shares outstanding. If done correctly, however, the cost is an investment. It generates a return. A diligent employee, who gets granted stock, can create value for the company in excess of the stock granted. Likewise, a network participant can create value for the protocol in excess of the value of the tokens granted.

The return generated from the stock or tokens granted is not known until much later. Until then, a thoughtful share or token granting scheme is the best guideline of what may come: a great use of token distribution or abysmal dilution with no value to show for.

Not all token distribution is created equally

The tokens included in the FDMC calculation include all future token issuances. But not all token issuances are the same. Some tokens are issued to early adopters, some to the founding team and some to initial investors. Some tokens are issued to a protocol’s foundation for future use. These include tokens issued to a protocol’s treasury and ecosystem fund. They are tokens that will be spent on developing the network. Tokens earmarked for future investment in the network should not be included in the token outstanding figure.

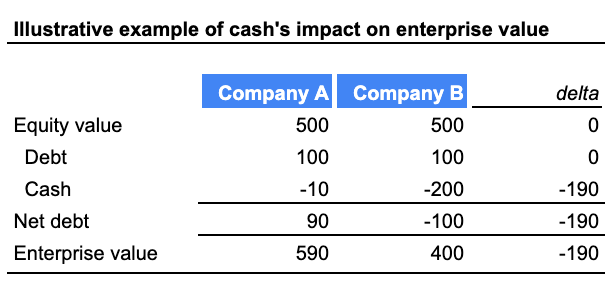

Tokens earmarked for future investment are equivalent to cash on a company’s balance sheet. Balance sheet cash reduces the overall value of a company. The overall value of a company is its enterprise value. The enterprise value reflects the value of all of the company’s assets. A portion of the enterprise value is a company’s equity value. For public companies, the equity value is its market cap. The other portion is its net debt. The net debt is the total debt less cash. The idea being that a company’s total assets were funded by equity and net debt. The table below illustrates how adding cash reduces a company’s enterprise value, all else being equal.

The value of tokens earmarked for investment is the token price multiplied by the number of tokens earmarked. That’s money that the protocol has to invest. It’s the equivalent of cash on a balance sheet.

The table below mechanically outlines the logic. The example in the table below outlines a protocol which has 500 tokens circulating. An additional 200 tokens will be issued to the treasury. The 200 tokens are earmarked for investing in the network. At a $5 token price the market cap and FDMC is $2,500 and $3,500 respectively. The 200 tokens earmarked for investment sitting in the protocol’s treasury are worth $1,000. The $1,000 value should reduce the overall value of the protocol, just like cash reduces the enterprise value of a company.

The tokens issued to treasury for investment can also be thought of as unissued shares of a company. The conclusion is the same as considering them as ‘cash.’ The shares that Apple may issue in the future are not included in its fully diluted market cap. Apple could sell shares to generate cash proceeds. The cash could then be invested in developing Apple products. The future value of those products would eventually be reflected in Apple’s market cap. Similarly, a protocol can issue tokens to its treasury to generate ‘cash’ proceeds to fund investing in its network. The difference is that for the protocol the ‘cash’ is money in its native token. It doesn’t actually need to sell shares to the market like Apple does to generate proceeds. In this case, the protocol is more like the Federal Reserve, it issues more money to pay for stuff. The logic still holds, those future token issuances for investment should not be included in the fully diluted tokens outstanding, just like future Apple share issuances aren’t.

The difference is flexibility

The reason protocols have such a large number of tokens outstanding from the outset is their rigid structure. Companies can freely issue and buy back shares. They need approval from their board and ultimately shareholders. But it’s relatively easy compared to protocols trying to issue and burn tokens.

From the outset protocols need to determine how many total tokens will be issued and when. It’s a “set it in stone day one mentality.” Companies and the Federal Reserve don’t operate with that rigidity. A company’s share count and the amount of US dollars in circulation ebbs and flows depending on market dynamics. A protocol needs to disclose a set number of tokens because its tokens are used as a monetary value to remunerate network contributors. If the number of tokens is not set in stone, then participants worry that the monetary value they’re rewarded in will lose its value due to token inflation. The cost of alleviating the concern is an inflexible token structure.

The result is overstated FDMC

Some protocols have overstated FDMC. The token figure used to calculate FDMC includes tokens issued to a protocol’s treasury for network investment. The enlarged token outstanding figure produces an overstated FDMC. The knock on effect is more expensive valuation multiples.

Arbitrum and Optimism, for example, have overstated FDMC. Their FDMC includes the total number of tokens that will ultimately be issued. In both cases, however, a significant number of tokens are issued to the treasury or equivalent. They are earmarked to be used to invest in the ecosystem. Removing these tokens from total tokens outstanding yields a more accurate adjusted token supply and hence adjusted market cap.

The table below illustrates the adjustment that should be made to Arbitrum and Optimism tokens outstanding. The adjusted token supply is 45% lower than the fully diluted figure.

So what’s the right token supply figure?

Circulating supply is sort of correct. It captures how many tokens are currently issued. But it misses the impact of future token issuance. Fully diluted supply is also somewhat correct. It captures how many tokens will eventually be issued. But it fails to adjust for tokens issued to the treasury. An adjusted token supply figure is most accurate. The adjusted figure starts with the fully diluted figure and nets out the tokens issued to the treasury.

One thing is for sure, the fully diluted market cap figure is misleading. Instead of inflating the market cap of a protocol based on future token issuance, a discerning analyst should handicap the existing valuation by the dilutive impact of future issuances.

Stay curious.

Don’t forget to hit the “♡ Like” button!

♡ are a big deal. They serve as a proxy for new visitors and feed into Substack’s algorithm that distributes my articles to all Substack readers.

Better yet…share this article with your crypto community.

It’ll show how on the ball you are ;)

Follow me on Twitter @samuelmandrew for my latest takes.

Idk man, fdv was only used as a quick way to normalize m.cap with token distribution when one compered between two or more tokens.

In that sense it’s was a valuable method

Killing it lately Sam. This was really helpful as I've been struggling to compartmentalize how treasury holdings could be better considered. I'm totally in the camp of mentally discounting the FDMC, I've always hated that getting thrown around.